There are a number of imperative methods for asking for permission to use

powerful features like location access in web apps. These methods come with a

number of challenges, which is why the Chrome permissions team is experimenting

with a new declarative method: a dedicated HTML

element is in origin trial from Chrome 126, and ultimately we hope to

standardize it.

Imperative methods for requesting permission

When web apps need access to

powerful features, they

need to ask for permission. For example, when

Google Maps requires the user’s location using the

Geolocation API,

browsers will prompt the user, often with the option to store that decision.

This is a

well defined concept

in the Permissions specification.

Implicitly ask on first use versus explicitly request upfront

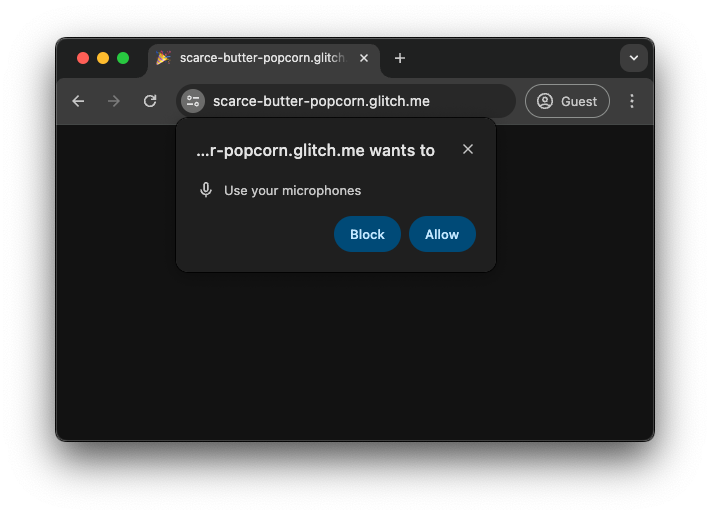

The Geolocation API is a powerful API and relies on the implicitly ask on first

use approach. For example, when an app calls the

navigator.geolocation.getCurrentPosition()

method, the permissions prompt automatically pops up upon the first call.

Another example is

navigator.mediaDevices.getUserMedia().

Other APIs, like the

Notification API or

the

Device Orientation and Motion API,

commonly have an explicit way to request permission through a static method like

Notification.requestPermission()

or

DeviceMotionEvent.requestPermission().

Challenges with imperative methods for asking for permission

Permission spam

In the past, websites could call methods like

navigator.mediaDevices.getUserMedia() or Notification.requestPermission(),

but also navigator.geolocation.getCurrentPosition() immediately when a website

was loaded. A permission prompt would pop up before the user had interacted with

the website. This is sometimes described as permission spam and affects both

approaches, implicitly asking on first use as well as explicitly requesting

upfront.

Browser mitigations and user gesture requirement

Permission spam led to browser vendors requiring a user gesture like a button

click or a keydown event before showing a permission prompt. The problem with

this approach is that it’s very difficult, if not impossible, for the browser to

figure out if a given user gesture should result in a permission prompt to be

shown or not. Maybe the user was just clicking on the page in frustration

anywhere because the page took so long to load, or maybe they were indeed

clicking on the Locate me button. Some websites also became very good at

tricking users into clicking on content to trigger the prompt.

Another mitigation is adding prompt abuse mitigations, like completely blocking

features to begin with, or to showing the permission prompt in a non-modal, less

intrusive manner.

Permission contextualization

Another challenge, especially on big screens, is the way the permission prompt

gets commonly displayed: above the

line of death, that

is, outside of the area of the browser window that the app can draw onto. It’s

not unheard of that users would miss the prompt at the top of their browser

window when they just clicked a button at the bottom of the window. This problem

is often exacerbated when browser spam mitigations are in place.

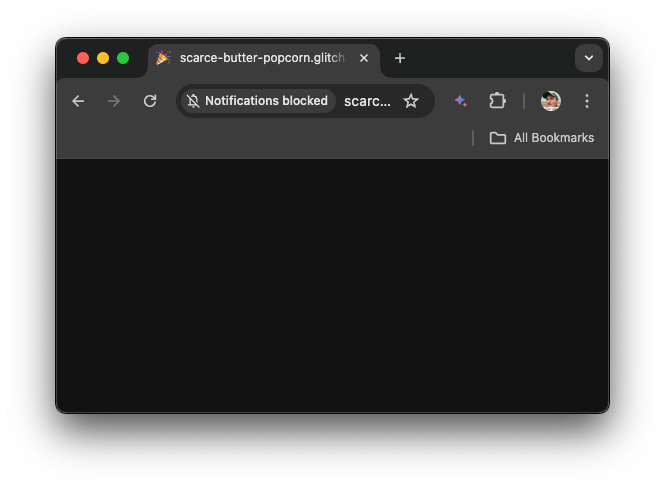

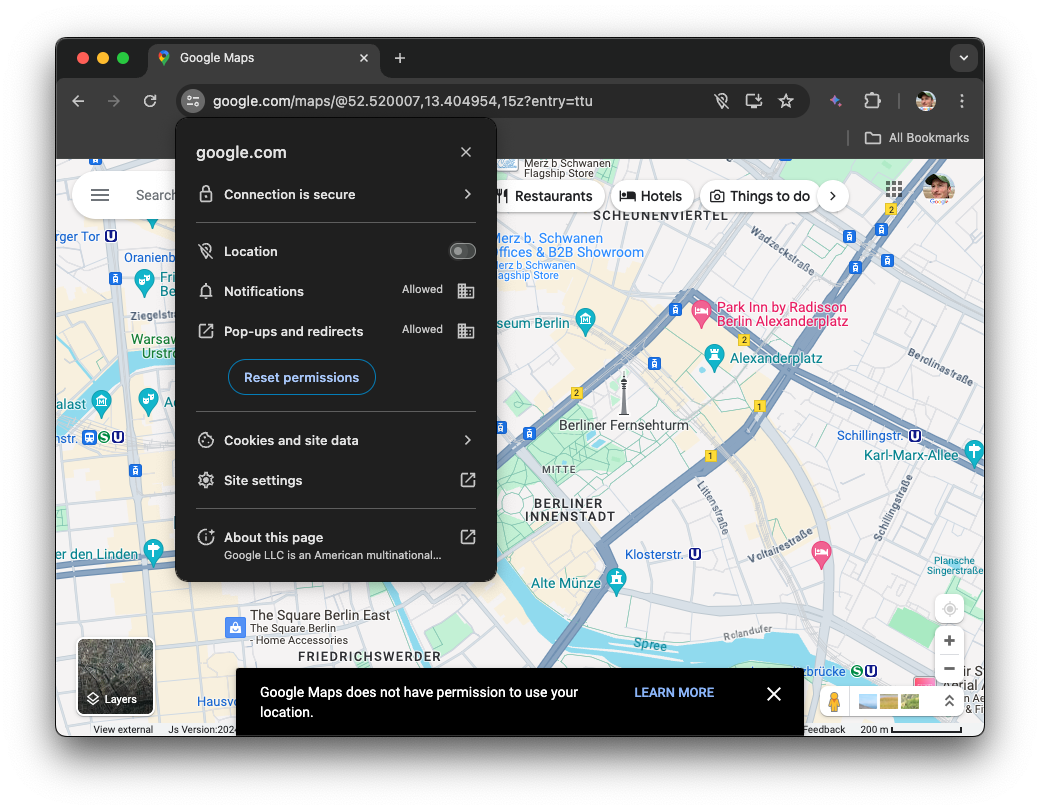

No easy undo

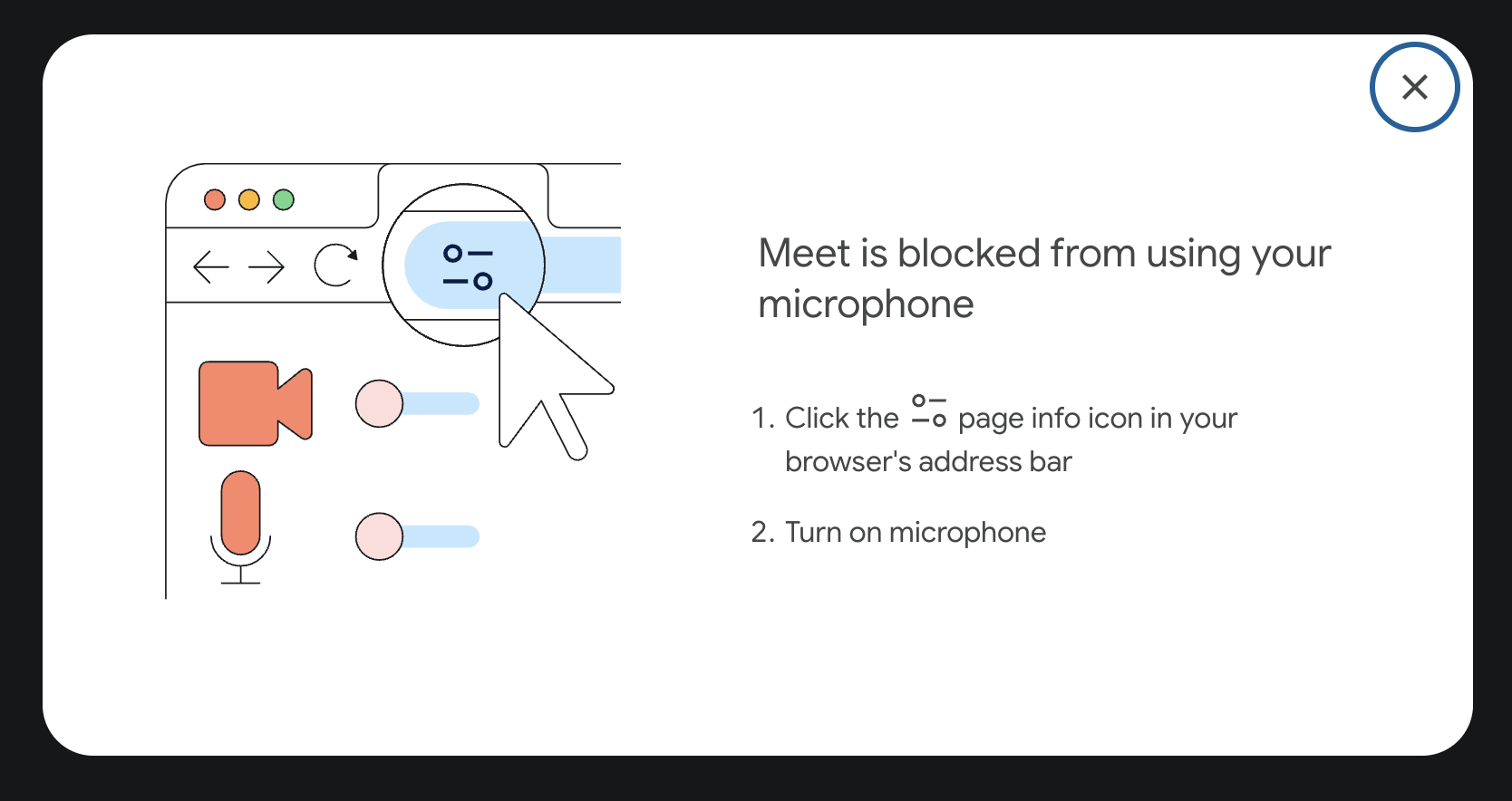

Finally, it is too easy for users to navigate themselves into a dead-end. For

example, once the user has blocked access to a feature, it requires them to be

aware of the site information drop-down where they can either Reset

permissions or toggle blocked permissions back on. Both options in the worst

case require a full reload of the page until the updated setting takes effect.

Sites have no ability to provide an easy shortcut for users to change an

existing permission state and have to painstakingly explain to users how to

change their settings as shown at the bottom of the following Google Maps

screenshot.

If the permission is key to the experience, for example, microphone access for a

video conferencing application, apps like Google Meet show intrusive dialogs

that instruct the user how to unblock the permission.

A declarative

To address the challenges described in this post, the Chrome permissions team

have launched an origin trial for a new HTML element,

element lets developers declaratively ask for permission to use, for now, a

subset of the powerful features available to websites. In its simplest form, you

use it as in the following example:

It’s still being actively debated

whether

element or not. A void element is a self-closing element in HTML that cannot

have any child nodes, which, in HTML, means it may not have an end tag.

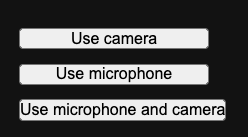

The type attribute

The

type

attribute contains a space-separated list of permissions you are requesting. At

the time of this writing, the allowed values are 'camera', 'microphone', and

camera microphone (separated by space). This element by default renders

similar to buttons with barebones user agent styling.

The type-ext attribute

For some permissions that allow for additional parameters, the

type-ext

attribute accepts space-separated key-value pairs, like, for example,

precise:true for the geolocation permission.

The lang attribute

The button text is provided by the browser and meant to be consistent, so it

cannot be directly customized. The browser changes the language of the text

based on the inherited language of the document or the parent element chain, or

an optional

lang

attribute. This means that developers don’t need to localize the

element themselves. If the

trial stage, several strings or icons may be supported for each permission type

to increase the flexibility. If you’re interested in using the

element and need a specific string or icon, get in touch!

Behavior

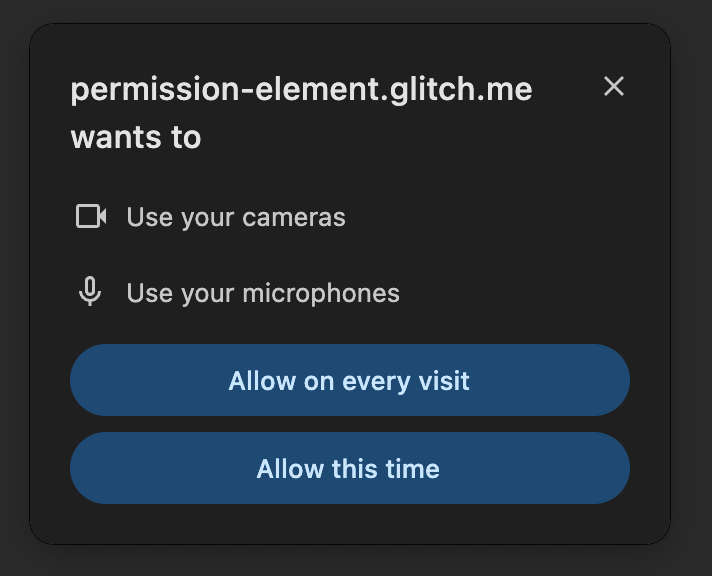

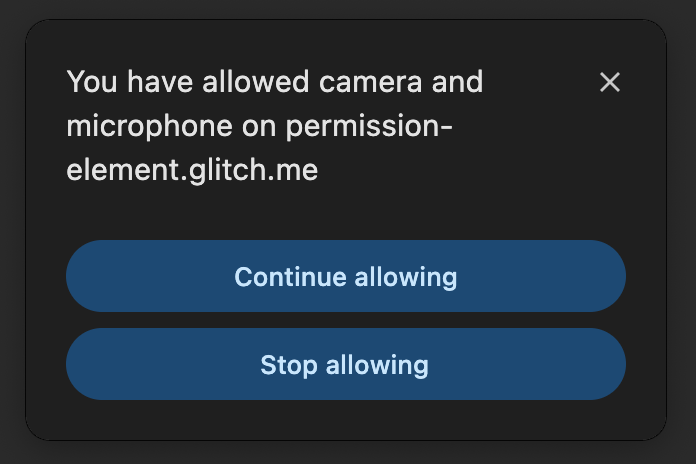

When the user interacts with the

various stages:

-

If they hadn’t allowed a feature before, they can allow it on every visit, or

allow it for the current visit.

-

If they had allowed the feature before, they can continue allowing it, or stop

allowing it.

-

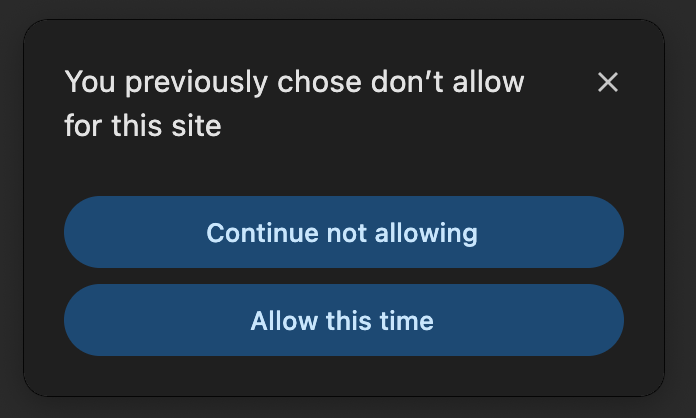

If they had disallowed a feature before, they can continue not allowing it, or

allow it this time.

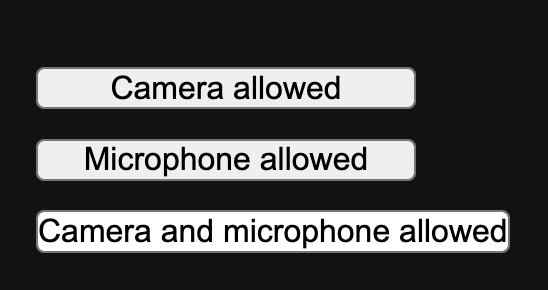

The text of the

status. For example, if permission was granted to use a feature, the text

changes to say the feature is allowed. If permission first needs to be granted,

the text changes to invite the user to use the feature. Compare the earlier

screenshot with the following screenshot to see the two states.

CSS design

To ensure users can easily recognize the button as a surface to access powerful

capabilities, the

restrictions don’t work for your use case, we’d love to hear about

how and why! While not all styling needs can be accommodated, we are hoping to

discover safe ways to allow more styling of the

origin trial. The following table details some properties that have restrictions

or special rules applied to them. In case any of the rules are violated, the

attempts to interact with it will result in exceptions that can be caught with

JavaScript. The error message will contain more details on the detected

violation.

| Property | Rules |

|---|---|

|

|

Can be used to set the text and background color, respectively. The contrast between the two colors needs to be sufficient for clearly legible text (contrast ratio of at least 3). The alpha channel has to be 1. |

|

|

Must be set within the equivalent of small andxxxlarge. The element will be disabled otherwise. Zoomwill be taken into account when computing font-size. |

|

|

Negative values will be corrected to 0. |

margin (all) |

Negative values will be corrected to 0. |

|

|

Values under 200 will be corrected to 200. |

|

|

Values other than normal and italic will becorrected to normal. |

|

|

Values over 0.5em will be corrected to0.5em. Values under 0 will be corrected to0. |

|

|

Values other than inline-block and nonewill be corrected to inline-block. |

|

|

Values over 0.2em will be corrected to0.2em. Values under -0.05em will becorrected to -0.05em. |

|

|

Will have a default value of 1em. If provided, themaximum computed value between the default and the provided values will be considered. |

|

|

Will have a default value of 3em. If provided, theminimum computed value between the default and the provided values will be considered. |

|

|

Will have a default value of fit-content. If provided,the maximum computed value between the default and the provided values will be considered. |

|

|

Will have a default value of three times fit-content. Ifprovided, the minimum computed value between the default and the provided values will be considered. |

|

|

Will only take effect if height is set toauto. In this case, values over 1em will becorrected to 1em and padding-bottom will beset to the value of padding-top. |

|

|

Will only take effect if width is set toauto. In this case, values over 5em will becorrected to 5em and padding-right will beset to the value of padding-left. |

|

|

Distorting visual effects won’t be allowed. For now, we only accept 2D translation and proportional up-scaling. |

The following CSS properties can be used as normal:

font-kerningfont-optical-sizingfont-stretchfont-synthesis-weightfont-synthesis-stylefont-synthesis-small-capsfont-feature-settingsforced-color-adjusttext-renderingalign-selfanchor-name aspect-ratioborder(and allborder-*properties)clearcolor-schemecontaincontain-intrinsic-widthcontain-intrinsic-heightcontainer-namecontainer-typecounter-*flex-*floatheightisolationjustify-selfleftorderorphansoutline-*(with the exception noted before foroutline-offset)overflow-anchoroverscroll-behavior-*pagepositionposition-anchorcontent-visibilityrightscroll-margin-*scroll-padding-*text-spacing-trimtopvisibilityxyruby-positionuser-selectwidthwill-changez-index

Additionally, all logically equivalent properties can be used (for example,

inline-size is equivalent to width), following the same rules as their

equivalent.

Pseudo-classes

There are two special pseudo-classes that allow for styling the

element based on the state:

:granted: The:grantedpseudo-class allows for special styling when a

permission was granted.:invalid: The:invalidpseudo-class allows for special styling when the

element is in an invalid state, for example, when it is served in a

cross-origin iframe.

permission {

background-color: green;

}

permission:granted {

background-color: light-green;

}

/* Not supported during the origin trial. */

permission:invalid {

background-color: gray;

}

JavaScript events

The

Permissions API.

There are a number of events that can be listened for:

-

onpromptdismiss: This event is fired when the permission prompt triggered by

the element has been dismissed by the user (for example by clicking the close

button or clicking outside the prompt). -

onpromptaction: This event is fired when the permission prompt triggered by

the element has been resolved by the user taking some action on the prompt

itself. This doesn’t necessarily mean the permission state has changed, the

user might have taken an action that maintains the status quo (such as

continuing to allow a permission). -

onvalidationstatuschange: This event is fired when the element switches from

being"valid"to"invalid". The element is considered"valid"when the

browser trusts the integrity of the signal if the user were to click it, and

"invalid"otherwise, for example, when the element is partly occluded by

other HTML content.

You can register event listeners for these events directly inline in the HTML

code

(

or using addEventListener() on the

following example.

Feature detection

If a browser doesn’t support an HTML element, it won’t show it. This means that

if you have the

browser doesn’t know it. You may still want to detect support using JavaScript,

for example, to create a permission prompt triggered through a click of a

regular .

if ('HTMLPermissionElement' in window) {

// The `` element is supported.

}

Origin trial

To try the

sign up for the origin trial.

Read Get started with origin trials for

instructions on how to prepare your site to use origin trials. The origin trial

will run from Chrome 126 to 131 (February 19, 2025).

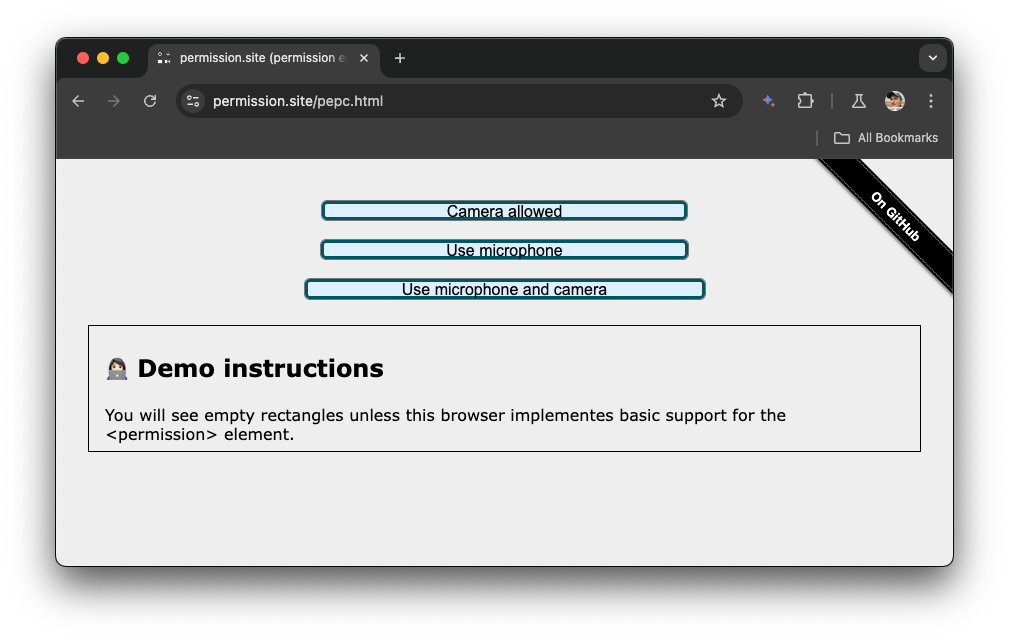

Demo

Explore the demo and check out the source code on GitHub. Here’s a screenshot of the experience on a supporting browser.

Feedback

We would love to hear from you how

free to respond to one of the

Issues in the repository, or file a new

one. Public signals in the repo for the

it.

FAQ

- How is this better than a regular

paired with the Permissions

API? A click of ais a user gesture, but browsers have no way of

verifying that it’s connected to the request for asking for permission. If the

user has clicked a

related to a permission request. This allows the browser to facilitate flows

that otherwise would be a lot more risky. For example, allowing the user to

easily undo the blocking of a permission. - What if other browsers don’t support the

non-supporting browsers, a classic permission flow can be used. For example,

based on the click of a regular. The permissions team are also

working on a polyfill. Star the GitHub repo

to be notified when it’s ready. - Was this discussed with other browser vendors? The

was actively discussed at W3C TPAC in 2023 in a

breakout session. You

can read the

public session notes.

The Chrome team has also asked for formal Standards Positions from both

vendors, see the Related links section. The

element is an ongoing topic of discussions with other browsers and we’re

hoping to standardize it. - Should this actually be a void element? It’s still being

actively debated

whether

element or not. If you have feedback, chime in on the Issue.

Acknowledgements

This document was reviewed by

Balázs Engedy,

Thomas Nguyen,

Penelope McLachlan,

Marian Harbach,

David Warren, and

Rachel Andrew.