Listen and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

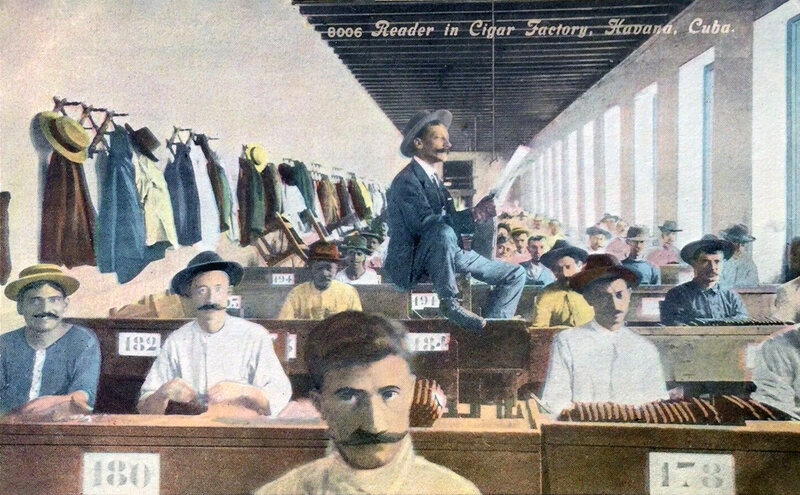

Dylan Thuras: Cuba and cigars have a longer history than you might realize. Indigenous Caribbeans have been using tobacco for millennia. In the early 1800s, under Spanish colonial rule, the first cigar factories opened. And eventually in these cigar factories, you would walk in and the smell of tobacco would waft through the air. The torcedores would sit at these neat orderly desks, rolling cigar after cigar. And you would hear something maybe unexpected in these factories. While people rolled cigars, you would hear the sound of a daily news report, or maybe a poem or a novel, being read aloud. Read aloud by a person known as the reader. The cigar reader is a tradition that is still held by a handful of people, and came from this fundamentally revolutionary set of ideas. Ideas that would shape Cuba in many profound ways.

I’m Dylan Thuras, and this is Atlas Obscura, a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Today, I’m talking with Eliot Stein. Eliot is a journalist, and he has traveled across the world, finding and reporting on these disappearing customs. These traditions where there are just a few people still maintaining them. Eliot chronicled this in his book, Custodians of Wonder: Ancient Customs, Profound Traditions, and the Last People Keeping Them Alive.

This is an edited transcript of the Atlas Obscura Podcast: a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Find the show on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

Dylan: Hi, Eliot. Thanks for coming to the show again.

Eliot: Thanks so much for having me, Dylan.

Dylan: Last time, we talked about this tradition of weaving these giant Incan rope bridges out of fiber, and they cut them down and remake them every year. And so, we are moving to a different part of the world to talk about a very different tradition with a different kind of history and impact. Let’s talk about Cuban cigars. Just for a very sensory question, what does it smell like in one of those buildings?

Eliot: It smells like damp, decomposing leaves. In autumn in the United States, when you rake leaves into a pile and set it on the street, and then maybe after a rainstorm and you’re close to it, it smells much like that. It’s sort of damp, dank, it’s stuffy, and it’s completely silent except for the noise of the reader and the sound, that kind of beautiful, cacophonous sound of these curved knives called chavetas, which are hitting a wooden table.

Dylan: They feel like one of these things that are still made by hand. They don’t seem to have maybe been totally industrialized, at least maybe not in Cuba. And you went and saw kind of firsthand what happened in a cigar factory in Havana at La Corona. What is it like to actually visit a cigar factory in modern-day Cuba? What’s happening in there?

Eliot: Visiting a cigar factory in modern-day Cuba, I imagine, is very similar to visiting a cigar factory in Cuba a hundred years ago. Time is a funny thing in Cuba, as anyone who’s listening and has gone to Cuba knows. But you go into these giant, hulking warehouses. The windows are sort of sealed. You don’t want these very valuable tobacco leaves to get too moist, to get too damp. And there are hundreds and hundreds of rollers called torcedores, who are rollers, sitting in what look like 19th century school desks. And they’re all facing the front of a room. And as they’re monotonously doing their choreography of roll, cut, lick, over and over and over again, they’re listening to a lector. And a lector is literally a reader. And there is an official reader in a factory, traditionally. And their job is to do just that. They read newspapers every day. They recite poetry. They read announcements to the workers. And over the history of this job, which is more than 150 years old, there have been some remarkable consequences.

These readers and these rollers, through their very intimate relationship, they formed some of the first trade unions in Cuba. They formed some of the first guilds. It is not an exaggeration to say we’re some of the most instrumental individuals in leading to Cuban independence against the Spanish from the 1860s to the 1890s. And then in the decades afterwards, they were fundamental in forming Cuba’s national identity. And so I didn’t know any of this before I got there, or at least before I started researching the story. But it’s, you know, everyone knows about Cuban cigars, but almost no one knows about one of the most important jobs in the cigar making process. And that’s what I went there to research and understand.

Dylan: Almost everyone is doing this job of being a roller. You know, the vast majority of the people in this factory have a very straightforward job, which is to roll cigars. But then there is this one job, this reader, and it seems like there’s a sort of schedule of different types of readings that can happen. Maybe you could talk me through what might be read during a typical day.

Eliot: Yeah, so one of the people that I profiled, and I met as many readers as I could in Cuba, and there aren’t that many that still exist, but one of them has a fittingly poetic name. Her name is Odalys de la Caridad Lara Reyes. Yeah, so her day starts at 6:00 a.m. She boards a bus from her home outside of Havana and gets into the office at about 7:00, 7:15. She then muffles through a stack of newspapers on her desk, which are all state-sponsored in Cuba, as everything is, and she decides what it is that she wants to read. But her day starts when the torcedoras, the rollers, arrive, and that’s at about 8:15.

She recites poems that she’s written for individuals celebrating their birthdays. I should say that of the 300-some rollers that she works for, she knows all of their names, she knows all of their birthdays, she knows all of their family members. So she reads announcements for them, whether it’s individuals welcoming children, individuals who have requests for moments of silence for those who have recently lost someone. She then transitions to practical advice based on topics that the workers have asked her about, and this can be everything from how to calm a screaming newborn to how to talk to your teenager about dating, you name it. It’s really at the worker’s discretion. Then at about 8:45, she segues into accounts of historical figures, which often relate to the novel that she’s reading. So for instance, when I went there, she was reading The Count of Monte Cristo, which happens to be one of the most popular novels that readers read and that workers love. And so while she’s reading that, she might read a profile of Joan of Arc, and then at 10:00, she turns to national and international news.

I asked her, in the 30 years that you’ve been doing this, what are some of the most meaningful news announcements that you’ve read to your workers? And she recalled the time in 1998 when Pope John Paul II was arriving in Cuba, and how she read this out loud, and this is how the workers discovered this, and people burst into tears. And then similarly, back in 2016, she had to announce the loss of Cuba’s titan patriarch, Fidel Castro. And similarly, the whole room just erupted in sadness. So she’s got a very full day, and then in the afternoon, she reads her novel, and by about 2:00 or 3:00 p.m., that’s when the workers shuffle out. But it’s not just a transactional kind of I read, you listen sort of relationship. And when I was shadowing her, and I’d go to her small office, which is a small desk under a mammoth poster of Fidel Castro and Che Guevara, people would come in and out for all kinds of practical advice. This is really sort of not so much a literal reader, but kind of a mother figure, a leader. And when you trace the history of this profession, that’s always how it’s been. It’s kind of a community organizer of sorts.

Dylan: Somewhere between a one-person public radio station, and an HR department, and a leader, or a figurehead. That’s a fascinating combination of things. Why did this happen? Why did this job come to exist?

Eliot: That’s a great question. There’s a tobacco museum in Havana, and I was talking with one of the directors in one of my first interviews, and I sort of asked that question as well. And she had a wonderful quote, which she said, “you can’t understand Cuba without understanding tobacco.” And so as a brief history lesson, Columbus arrived in 1492. He noticed that the indigenous Taino people were smoking this thing that they call tobacco, spelled with a K. And that’s how we get the name. But they rolled it into this kind of cylindrical shape. And he called it, in his journal, he called it kind of a half burnt weed. So Columbus is curious about what this is. He collects a few leaves. He sends it back to Spain, because he’s working for the Spanish. And people go absolutely nuts for it. As people who’ve never smoked tobacco before, it becomes addictive. Columbus obviously enslaves the Taino, and the rest is history. But by about the 16th century, you have Criollos, ethnically Spanish people, but who were born in Cuba. They begin farming the stuff. But the Spanish crown taxes it very, very heavily. So as a way of kind of avoiding these taxes, tobacco products reach to the far corners of the island. In the 1700s, the Spanish crown does this terrible thing where they basically say, every bit of tobacco that’s grown in Cuba, you have to sell to us at a discount. We’re going to ship it to Spain. We’re going to roll it and completely cut you out of the process. So we have the exclusive right to sell the stuff. Sometime in the early 1800s, people discover that actually, this tobacco product, it survives a transatlantic voyage much better when you roll it and when you actually form a cigar than when you ship dried leaves across the ocean. So at that point, Cubans or people living in Cuba are finally allowed to take control of this product themselves.

But at this time, ethnically, Cuba looked very similar to how it looks today. You have the Criollo people of Spanish descent, you have West Indians, you have people of African descent. It’s not only a melting pot of cultures, but this kind of bubbling cauldron of ideas and anger against the Spanish crown. And so in 1866, this guy named Saturnino Martinez, that history is completely forgotten, comes up with this beautiful idea. At this time, the ethnic Cubans, the Criollos are completely disenfranchised compared to the peninsulares, which are kind of the Spanish elites. Education is bad. They’re not allowed so many things. He has this idea of: while we’re doing this monotonous job for six, seven, eight hours a day, why don’t we get some person to awaken their consciousness, to increase their education, and to expand their worldview? We’re going to call them a lector, and you put them in front of the room, and they are going to read books, talk about the news. And he even created newspapers called El Siglo and La Aurora, which means the dawn, kind of as a nod to the intellectual awakening that he was hoping to inspire, so that these readers could read them.

And at first, these weren’t professional readers or anything like that. They would rotate from the rollers, where one person would have a turn on Monday, the next person on Tuesday, and they would just get up there and read. And obviously, not everyone knew how to read, hence the idea in itself, right? Only about 10 percent of people at this time knew how to read. So it was a pretty small pool that you’re picking from, right? One of the lovely things about the early tradition is that because every roller, every torcedor, had a certain quota that they had to hit, when it was that person’s turn to read, everyone else would chip in, make more cigars, and give it to that day’s reader so that he wouldn’t fall behind. So these people began reading, and within six months of the start of the reading, this tradition had expanded to every single cigar factory in Cuba. And to give you a sense of how many cigar factories there were at the time, in 1865, there were 500 tobacco factories in Havana alone, which is a remarkable statistic. So obviously, the seemingly quaint roll became a lightning rod for the Spanish crown. And just six months after this whole thing began, Spanish elites, the peninsulares, tried to shut it down. They tried to muzzle the reader almost as soon as it started.

Dylan: One of the things that I think is so interesting about this is you could see this starting as, oh, this is just like kind of nice, and then evolving into kind of a political thing. But it seems to have really started from its very base as, okay, this is a way to educate and maybe even radicalize the public, the worker, about the Spanish crown, about what’s going on. I can see why the Spanish were not so excited about this.

Eliot: For sure. In the 1800s, newspapers were sort of the front lines of reform, of change. But you know, the Saturnino Martinez who came up with this idea, he needed a literal mouthpiece to amplify the call, to amplify the change. And so this is where this came from. So six months after this starts, the Spanish crown has this insane idea where they make it illegal for Cubans to gather and to read together unless that reading is directly related to your job. So they effectively ban reading, which is …

Dylan: Always a good sign.

Eliot: Always a good sign. Every country wants that. That’s a huge moment in Cuban history that not many people know about. This continues through the Ten Years’ War, which is with Spain. That is a terrible, terrible decade for Cubans. It’s a mass exodus effectively. And so that leads to another fascinating part of this tradition where you basically have the birth of Florida. So you have a mass exodus from this island. These readers, these rollers, they all migrate to Key West, which at this time was a pirates’ lair. There was no one there. And within a couple of years, it becomes the largest city in Florida. So you have these radical individuals from Cuba. Basically, when the tradition stopped forcibly in Cuba, they just relocate 90 miles north to Key West. And they continue doing this, but it only gets more and more radical. They then migrate just outside of Tampa Bay to a place that still exists called Ybor City.

And at a certain time in the 1880s, it was actually the cigar capital of the world. They were cranking out 500 million cigars every year. And it was all Cuban exiles. You had some Italians, you had some West Indians, but it was effectively Cubans. And so long story short, when we get to Ybor City, you have some of the most pivotal individuals in the Cuban independence movement who are working there. One of the most popular things that the readers read in Ybor City was this thing called the Patria, which was a newspaper started by a guy named Jose Marti. Jose Marti is basically the Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and George Washington all together of Cuba. He’s known as sort of the apostle of Cuban independence. He was born in Cuba. He was threatened with death, escaped to New York. And from New York, he creates this newspaper called Patria, which is all about Cuban revolution.

He becomes so beloved by the readers and workers that they pool their money together and invite him to come down to Florida. He makes 20 trips down to Florida between 1891 and 1894. And each time he comes, he’s accompanied by a huge entourage of lectors, of readers. And they’re the ones who introduce him. They’re the ones who basically secure his safety. They’re the ones who literally finance his trips. And he makes some of his most stirring calls for Cuban independence, including the famous Cuba Libre speech, which not only gave us a drink, but also Cuban independence from the lector’s podium in Florida. And as time evolves in 1894, not only are workers putting aside part of their wages to finance his trips, but to secure weapons for the forthcoming revolution. And these readers and workers, they go on the front lines, in the battle field, later.

Dylan: What’s so amazing about this story is that I think everyone is sort of at least vaguely aware of the recent revolutionary history of Cuba. Of Castro, of the fight for independence, and even Cuban exiles in Florida. Like the number of weird sort of just rhyming pieces of this story that then sort of play out in some other way into the future, there’s just, I did not realize in some ways how much of the more recent history of Cuba has this kind of resonant parallel echo in this older history of Cuba.

Eliot: Totally. And as someone who admittedly knew very, very little about Cuba, and certainly less about cigars, I mean, this was an awakening for me that—it was, you know, mesmerizing.

Dylan: For me, it also totally changes, like—okay, yes, I associate cigars with Cuba, I associate them with Castro, but they’re kind of a prop. It feels like, okay, yeah, they’re there because it’s part of the economy and Castro smoked cigars. But in this telling of the story, or this understanding of it, obviously, tobacco, cigars, and then this space for communication within the factory, it puts them absolutely central to the story of Cuban revolution, Cuban independence, and everything, all those sort of things that would come later. So talk to me about what’s happening today. It sounds like there are a few of these readers left. I’m a little bit, if I’m honest, surprised that this wasn’t all converted over to state-run radio at some point, and there’s at least some lectors still serving.

Eliot: Yeah, for sure. You know, once this tradition goes from Cuba to Florida, by necessity, right, because it was effectively muzzled by the Spanish, it also spreads to other places. Like, for a while, the Dominican Republic employed cigar readers. For a while, Puerto Rico did as well. Today it exists only in Cuba, and it exists in a very, very small quantity compared to what it used to. People at the state-run tobacco agency told me that in 2009, it was estimated that 250 readers remained in Cuba. Ten years later, there were just 150 of them, and today there’s just 50 left. In Havana, which, as I was saying, at one point had 500 cigar factories and every single one employed a reader, today there are just three left. And Odalys de la Caridad, she’s effectively the last reader who’s been there for a while. This is now her 33rd year of service. But yeah, to your great point, you know, in the 1930s, cigarettes became very, very popular, because industrialized cigarettes, I should say. So that replaced a lot of the demand for cigars. Then you obviously had radio that was introduced, which kind of silenced the reader even more. And so today, in a lot of the places where there used to be readers, some of the workers obviously still want them, but some of them are like, actually, could we just do 30 minutes of reggaeton on a tinny radio? And you have this once-upon-a-time tradition that has effectively created Cuba and helped create its identity that is slowly more and more and more fading away.

Dylan: And Odalys, the reader we talked about in the beginning of this conversation, what did she tell you about what it’s like for her today as a reader?

Eliot: She’s served 33 years, and she still works at the Corona factory, which is the largest factory in all of Cuba, and it’s located in Havana. You know, the way that she described it to me, and I should preface this by saying she was very cagey, and everyone who I talked to was very cagey, because you had this government agent right over you. And you know, my job as a journalist is not to poke and pry and push at the seams of something that is going to get someone in trouble in front of an agent. She told me a little bit about how you get this job, and it’s lovely. It’s sort of known as the only democratically elected job in Cuba. The way that it works is that, you know, you don’t post this on LinkedIn. You have a number of candidates who do trial runs by reading in front of the rollers, and they elect through a secret ballot whose voice is most pleasing, whose delivery is most inspiring, and she got the role. And she told me that over her decades of service, it’s effectively a family. She was hospitalized for a long time with coronavirus, and people came to visit her every day. This is what gives her a sense of purpose, gets her out of bed in the morning.

But then I met another individual who worked for even longer and was recently fired, which is almost unheard of in Cuba. You don’t easily get fired from things in an economy like Cuba. And the reason that she was fired was because she wanted to read things the way that she once was able to, but things were getting more and more and more strict. And the way that she was able to communicate this to me in front of the government agent—you know, I was asking her about what it was like to previously work there. She got quite emotional. The government agent said, let’s pause for a bit. He went outside to go smoke a cigar, of course. And then through a series of coded kind of gestures, through winking, through nodding, etc., she answered my questions and effectively let me know that she was pushed out. And this factory where she once worked no longer employs anyone for the same reasons, that it is becoming more and more strict to deliver honest information about what is happening. And that was very telling. So, you know, back to the director’s quote, she’s exactly right. You can’t tell the history of Cuba without understanding tobacco and more specifically readers.

Dylan: Yeah. There’s lots of cultures with, you know, storytelling traditions. This one feels really distinct to the Cuban story and Cuban history. And maybe this is—some part of me holds out hope that like this tradition will reassert itself in some other, you know, freedom loving way. I don’t know what that means exactly, but there’s just a beauty to it. There’s a beauty to the tradition. And to see how deeply interwoven it has been with the entire Cuban history going back, you know, 150 plus years, you know, is just fascinating. Thank you for telling us the story, Eliot.

Eliot: Thank you so much for having me.

Dylan: That was Eliot Stein. He is a journalist and the author of a fantastic book, Custodians of Wonder: Ancient Customs, Profound Traditions, and the Last People Keeping Them Alive. Eliot has come on the show a couple of times now to talk about these traditions. So if you’re curious about them, go and listen to the episode we did previously about the Q’eswachaka, sometimes called the Last Incan Bridge. It is an amazing tradition and one of the most incredible places I have ever been. So go check it out. We will put a link in the episode description.

Listen and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

Our podcast is a co-production of Atlas Obscura and Stitcher Studios. This episode was produced by Alexa Lim. The people who make our show include Doug Baldinger, Kameel Stanley, Johanna Mayer, Manolo Morales, Gabby Gladney, Amanda McGowan, Alexa Lim, Casey Holford, and Luz Fleming. Our theme music is by Sam Tindall.